Opinions of Peter Belmont

Speaking Truth to Power

|

Too much population, too much CO2, too much money lead to Egypt |

|

by Peter A. Belmont / 2011-02-06

| |||||||

|

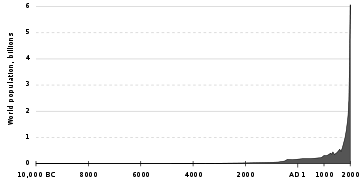

SUMMARY

The world system—comprising both natural systems and human systems—is one, and is finite. Human-kind, whether from hubris or ignorance or both, pretends otherwise. Those whose prayers include “The Lord, Our God, is One” (or similar assertions of essential one-ness)—and all others of any sort of good-will—should consider this essential oneness and essential finiteness when contemplating the way that humanity is overflowing the world. Where are the official representatives of the world’s religions when, today as never before, the world’s people must be made aware that humanity is rushing past limits set by nature—to our peril, to its peril, and arguably contrary to every religious teaching that calls on people to be custodians of the earth, or even to be friends of each other? And is it not the role of religion to speak truth to power? And if to speak truth, then, first, to learn the truth? And is not such speaking, such speaking of truth, such very difficult and unpopular speaking, more critical today than yesterday? And if not now then when? And if not our generation, then which generation? And, at this rate, how many more will there be? ESSAY Can the earth have too large a human population? To answer this question, I am afraid that I shall have to ramble, because it is a very big question, and a very important one. But here is my conclusion, so the reader may not be left in suspense: Well, the news is no news at all. The future will occur. It will take care of itself. Yes. But it will not be beneficial for humankind unless we take pains to make it so. And we have grown to put off today’s pains until the future. If earth can NOT have too large a human population, then humankind can safely continue as we have for many decades, recklessly increasing the world human population  as if there were no adverse consequence today, and none foreseeable, either for particular human grouplets locally, for humankind as a whole, or for the existing non-human elements of the world.[1] But if, to the contrary, excess human population does have (or even might have) seriously adverse consequences for the continued smooth operation of the world-system—comprising both environmental-systems and human-systems[2]—then it behooves us (humankind) to ask a different question: If we don’t really know the outcome of continued human population growth, then—given such early-warning signs as global warming and world-economic perturbations—is it not our prudent duty to stop it? Should we not, like the people of Egypt (January 2011 revolution), say, “We demand a change in government!” And, as the people of Egypt should have added, but did not, should we not add, “We demand a stop to human population growth and a beginning to human population reduction”? But do we know or even worry about how the immense and rapidly growing human population will affect the future? No. Humankind, and especially its political systems, are slow to respond to bad news—unless it can be cast as a military attack to be repulsed. The advice of on-coming human-caused climate change in 1950s and 1960s was ignored.[3] The predictions of global warming are much more widely supported in the scientific community today than they were in 1950, but even today, and even in the face of the dire predictions, human populations are doing nothing much to avert even the portion of global warming not yet irreversibly part of the earth’s future. What else is world overpopulation bringing us? Food scarcity can arise from too many mouths, excessive cost, changes in the weather, changes in world governance. Over many years, the total area of arable land for food production has been shrinking.[4]  Mostly that comes from overgrazing, deforestation, industrialization, and other causes and recently it has also come about from the taking of arable land out of food production in order to grow energy crops (bio-fuels). On the other hand, the productivity of land has increased due to the vastly increased agricultural use of petroleum transformed into fertilizers and pesticides: the so-called “green revolution”. But the “green revolution” merely placed additional pressure on petroleum availability, a known problem giving rise to $90 and $100 barrels of oil today (2-2011), and also, and far more importantly, adding to the world-wide production of CO2 and the rushing onset—now irreversible—of global warming. The “green revolution” was meant to be ameliorative. World starvation—then predicted—needed to be headed off, as a humanitarian matter. Thus the need for a “fix”. And, of course, the “quick fix” of the “green revolution” was not accompanied by a change of reproductive behavior (unless to increase it by adding to available food supplies). There was no realization that with the “fix” came a need to reduce the problem being fixed by reducing the population. (In this, the “green revolution” was similar to the introduction of public sanitation—sewers. The reduction of deaths was not accompanied by a reduction of live births. On the contrary. No-one thought then, and few have thought since, of reduction of human population—or even of reduction of human population rate of growth. “More is better” seems to be the idea. Except in elevator cars and subway cars. These places are small enough for people to recognize local over-population when it occurs.) The ill effects predicted for global warming remind us of the best-known result of quantum mechanics, namely, the uncertainty principle. If global warming is to bring us more frequent and more violent storms, what will be the local consequence? Will global warming’s storms be good for Australia or bad? Good for Chicago or bad? Good for Egypt or bad? We don’t know for sure. We are uncertain. But most people who think about the problem realize that uncertainty about detail does not mean there will be no unfortunate consequences. And the longer-range consequences predicted for global warming are changes in climates, changes in the length of growing seasons, changes in rainfall, changes in speed of melting of glaciers, changes in snowfall, snow depths, snow-melts, and river-volumes over time. A place where the rivers flow smoothly, with steady and predictable volume over the growing season, can support agriculture. If the same amount of water rushes past in a short time and cannot be saved, then that water cannot support agriculture. Perhaps this may lead to a way to save quick melting snow and severe rainfall into rapidly-being-depleted aquifers (natural ground-water storage systems), but I have read nothing of such possibilities. One of the measures of over population is a bit accidental. It arises from the enormous amount of money (or liquidity or credit or whatever it is that economists, banks, governments, and investors care so much about) which sloshes about in the world’s economic systems. Everyone who rejoices in possessing money wants a “return” on it. Except in the Islamic world—where paying interest on loans is forbidden—money-owning people act as if they had a right to receive “interest” on that money and the big ones—the big USA banks for instance—create whizz-bang “investment vehicles” to create the illusion that “interest” at agreeable rates is available to all who seek it; and this despite the finiteness of the world, the finite amount and value of land, of buildings, of the things of, ahem, underlying economic productiveness. The rapaciousness of this “interest-seeking” capitalism showed itself recently in the great USA-generated world financial crisis. The USA’s responses to that crisis include recent flooding of the world with dollars, making food more expensive in Egypt and everywhere else. The rapaciousness of capitalism—and the utter lack of environmental consciousness on the part of just about everyone—has led to a world-wide failure to address global warming, a phenomenon predicted by some as early as 1950, but generally ignored and now headed irreversibly toward horrors already suggested by floods and fires in Australia, higher average temperatures and weather anomalies world-wide, etc. So, if too much CO2 is leading to a crisis for humankind, why is it not addressed by everyone with a concern for the future—that is, by just about everyone? My guess is that, like so much else in “democratic politics” in the USA and elsewhere is that the leadership of these “democracies” (also sometimes called “oligarchies”) have very short time-lines of concern. That is, business cares about profits for a quarter or year or even decade, but not about the long-range future. And in our modern democracies, apart from businesses and “special interest lobbies”, no-one else is “minding the store.” Our politicians have so thoroughly given up on acting as responsible custodians of the future of the people (of their own countries and of the world at large), and have so far succumbed to being led around by the nose by these corporations and special interests, and have so far forgotten about the danger of making decisions with long-term consequences based solely on short-term concerns, that the future is left to take care of itself. Well, the news is no news at all. The future will occur. It will take care of itself. Yes. But it will not be beneficial for humankind unless we take pains to make it so. And we have grown to put off today’s pains until the future. And so the future will be very painful, indeed. ----------- [1] Recall the words of the Balfour declaration: “it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine”. ----------- [2] By human-systems I mean such things as economic systems, governments, agricultural-production systems, energy-production systems. ----------- [3] Better spectrography in the 1950s showed that CO2 and water vapor absorption lines did not overlap completely. Climatologists also realized that little water vapor was present in the upper atmosphere. Both developments showed that the CO2 greenhouse effect would not be overwhelmed by water vapor. Scientists began using computers to develop more sophisticated versions of Arrhenius’ equations, and carbon-14 isotope analysis showed that CO2 released from fossil fuels were not immediately absorbed by the ocean. Better understanding of ocean chemistry led to a realization that the ocean surface layer had limited ability to absorb carbon dioxide. By the late 1950s, more scientists were arguing that carbon dioxide emissions could be a problem, with some projecting in 1959 that CO2 would rise 25% by the year 2000, with potentially “radical” effects on climate. By the 1960s, aerosol pollution (“smog”) had become a serious local problem in many cities, and some scientists began to consider whether the cooling effect of particulate pollution could affect global temperatures. Scientists were unsure whether the cooling effect of particulate pollution or warming effect of greenhouse gas emissions would predominate, but regardless, began to suspect the net effect could be disruptive to climate in the matter of decades. In his 1968 book The Population Bomb, Paul R. Ehrlich wrote “the greenhouse effect is being enhanced now by the greatly increased level of carbon dioxide... [this] is being countered by low-level clouds generated by contrails, dust, and other contaminants... At the moment we cannot predict what the overall climatic results will be of our using the atmosphere as a garbage dump.” (ibid) ----------- [4] The first global survey of soil degradation was carried out by the United nations in 1988-91. This survey, known as GLASOD - for Global Survey of Human-Induced Soil Degradation, has shown significant problems in virtually all parts of the world. The yellow line in each panel shows the global cropland area per person. Obviously, this indicator is a function of two factors: human population and cropland area. It has shown a steady decline in the 30 years from 1961 to 1991, amounting to a decrease of between 20 and 30%. The figure illustrates the regional changes that have accompanied this global change. North and central America and the former USSR are regions with significantly higher cropland areas per capita. However, all regions, including these, have shown decreases. South America croplands have declined at a rate that is slower than the global average, while African per capita croplands have declined at a greater than average rate. (Ibid.) |

Comments:

| rivermonkey 2011-02-10 | |

| Ahhh...NPR. i stopped listening for news when they failed to cover the Iraq debacle properly. Now I only listen to music and Fresh Air as they more and more use idiotic pop cultural references to explain science and finance. There reliance on direct sound bytes from blockbuster movies to explain the mortgage meltdown for example. NPR stood for Now Pandering to Republicans in the last decade. |

Submit a comment, subject to review:

|

123pab.com | Top

©2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024 www.123pab.com |